ALWAYS MORE LAND AND OPPORTUNITY FARTHER WEST

In the late 1800's, the Link family had struggled for several decades with decreasing market prices and increasing production prices. That on-going financial challenge finally spurred the idea of homesteading - even as far away as California.

In the transition from one farm the family had operated for decades to a new one after his father's death, Charles, "C.U." suddenly stopped farming within just a few years after settling in. The farm appears to have been surrendered either fully or partially to creditors. That story was not unique, however. It was repeated thousands of times.

The second Link farm in Indiana, purchased in part based on Charles Ulysses Link’s share of proceeds from his nearby parents’ farm, would have gotten off to a rocky start. In addition to unrelenting pressure on profits for nearly 30 years, there had been an economic panic in 1893. Businesses suddenly failed by the thousands. 575 banks either failed or were forced to suspend operations for a time. Thousands of farm mortgages were “called.” Until the Great Depression, it was the nation’s worst and longest-lasting serious downturn.

Recovery for farmers did not begin until after the turn of the century. Edna (Link) Jones wrote in a letter written in the 1970's and looking back over most of her life that "the new farm was abandoned." That would have been after six years of working it and adding a new barn and a new home. For reasons she was not included in, but that today can be speculated, C.U. and Clara moved their family to Nappanee, IN and turned the farm over to other interests. There, in Nappanee, they rented a home, made “some investments on lots in town” and Charles worked various income streams. That is, until he could put together a new plan for farming again.

"In the winter [probably 1902-1903], Father heard of cheap land in California and went, and I think homesteaded on a tract of land, and intended that we should move there, but since water was not found we stayed in Nappanee and he bought some lots in the north part of town, just two houses from our Nappanee Mennonite Church, near the school house."

- Edna Link (Jones)

If the “homestead” in California produced no water, Charles would only have been out some registration fees, travel and the cost of digging test wells. Because it was also referred to as “cheap land” by Edna, it could also have been acquired by some other method. The short-lived adventure however, still demonstrated that like millions of others - many of them immigrants from Europe - the Pacific Coast was in their sights as a potential place to start over again. Opportunity to some was always compelling, always whispering in their ears, and almost always farther west. Charles seems to have been among them. And he responded to losing his and Clara’s farm by making a vow to start over further west.

Once C.U. was back in Nappanee, the family raised a garden on the lots they had purchased, which “produced a bounty,” according to Edna. A modern home followed, "with bathroom and basement," that “the family was proud of.” C.U.s father Jacob was an experienced carpenter who had supervised - and did much of the work with Jacob Beutler - building the Holdeman Mennonite Church in Wakarusa, and also their own farm home and outbuildings. Charles would have learned carpentry skills from Jacob and probably did much of the work on the Nappanee home himself, with help. He had probably also designed and built the home and barn others helped construct on their farm along the main road to Nappanee. Some help on their latest homesite may have come from Forest, who was by then in his teen years. Several of the Link children probably had minor roles.

Other 20th Century advances, such as their first encounter with a horseless carriage, seemed exciting to daughter Edna.

Edna recalled a family carriage outing, with,

"… Father tightening the rei[g]ns, and saying, 'everyone hold on tight! Here comes Coonie Walkman in his horseless carriage.’ It really did look much like a single buggy with no horse. Our horses shied, pranced and ran, but Father was able to hold them."

- Edna Link (Jones)

A friend of the family heard of “affordable, good farm land” available in Davison County, SD. C.U. and others met to discuss the opportunity, and then organized trips to the area to review the land. By the spring of 1906, Charles, with Clara’s apparent blessing, was ready to purchase a farm of 160 acres. The land was situated between Mt. Vernon and Mitchell, South Dakota.

The cost of the South Dakota land was $33 an acre. The home in Nappanee was sold immediately, and the trek to South Dakota began not long after. The state of South Dakota had only been ratified by Congress a little over six years before. It came into the union with North Dakota, and the two had previously formed a territory sectioned from the earlier Nebraska and Minnesota Territories, and leaving land to the west that became Idaho Territory earlier in a series of several boundary changes. The beautiful, Neoclassical statehouse in Pierre, SD, the capital, would not be completed for another four years.

In 1906, there were 6 million farms in America and 31 million persons living on those farms. Many were finding the Great American Desert was possible to farm, but at a high risk of crop failure. Weather was unpredictable, often violent, and not like Europeans had experienced. The High Plains experienced some of the most violent storms on the planet, both in winter and in summer.

The land was purchased. There were no buildings. But the land did come into Charles and Clara’s hands, and work had to start immediately to return to farming before their remaining funds failed. It was already spring and rapidly becoming urgent to bring in crops before the growing seasons expired for 1906. A place to shelter was rented in Mt. Vernon.

For their spiritual lives, there was no Mennonite church in Mt. Vernon to welcome them. The whole Link family this time attended the Methodist Church of Mt. Vernon. Today, there are several Mennonite churches in the county and general vicinity, but not in Mt. Vernon or Mitchell. Edna mentioned in her recollections that others from Indiana were involved in trips to the area. So it is likely that persons who were familiar with one another came to the area at the same time, perhaps helping each other.

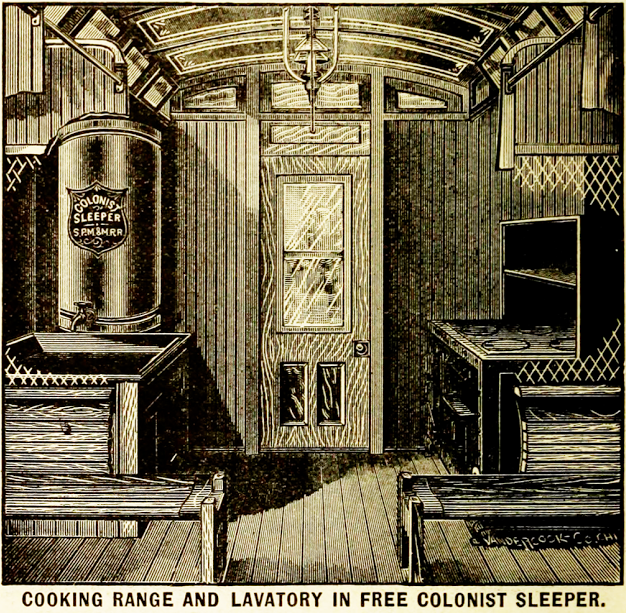

Colonist, or emigrant, sleeper car. CREDIT

"An immigrant [sic] railroad car was filled with household goods, implements, a horse and a cow. This [South Dakota] farm had no buildings, so we rented a place in Mt. Vernon while a house and barn were being built."

- Edna (Link) Jones

The emigrant or “colonist” car

With 12 million immigrants crossing parts of the United States from 1870 to 1900, railroads needed to respond with economical travel options. Sometimes they packaged railroad land with travel.

A colonist sleeping car (emigrant car) was designed to provide inexpensive long-distance transportation with accommodations that were spartan. A communal cooking area and lavatory were provided. Trips were often just a few days. Berths for sleeping were pulled down from overhead. Seating took place on unpadded wood benches. Privacy was limited.

Ancient symbol of well-being

Until the 1920’s, when Nazis applied a 45-degree angle to it to symbolize their reich, the swastika was a much-loved symbol in many places around the world. It represented calm, peace and well-being in several cultures, sometimes dating to pre-historic times. The swastika was featured on the Corn Palace of 1907 in Mitchell, near the Link farm.

One of the areas the Links would have visited would have been Mitchell, S. D. Over the years, a number of Corn Palace postcards with short messages accumulated in the correspondence of other Link family members outside the area. The swastika pictured on the 1907 Corn Palace was not a Nazi symbol at the time. It was a positive symbol used in many cultures.

The swastika developed in several parts of the world from the Southwestern cultures of prehistoric America to Hindu regions of Indus Valley near modern Pakistan. The symbol was used by the Ancient Greeks, Celts, and Anglo-Saxons, as well as many other cultures around the world, most often as a sign of well-being, balance or good luck.

1892 Corn Palace, Mitchell, SD.

First constructed in 1892, the Corn Palace was an attraction that quickly gained world fame. It was designed with the idea to display the crops grown by farmers in South Dakota in a dramatic fashion. Each year, the building was redecorated. Crops were used to fill mosaics on the outside of the building as well as murals on the inside. 3,500 of bushels of corn, wild oats, rye, straw, and wheat were applied.

The swastika on the 1907 Corn Palace was unintentionally an antecedent and coincidental link to deep divisions that would form in America. As two wars in Europe dragged immigrants who had been settled in some cases for several generations into a position of becoming suspect. That skepticism was often fronted by other Americans who may have emigrated to North America decades before, their travels going back to times even prior to the American Revolution.

It seems perhaps a strange distinction, one mostly of time. However, it makes more sense when considering groups that still often spoke the language of the country they came from and that practiced many cultural rituals in ways that separated those people from fully assimilating. It was at once a strength and a weakness. When conflict with Germany came to a pique in World War I, and just two decades later World War II, it was easy to see those who held on to German customs in America as perhaps also supporting their former country.

German-Americans were nearly unified in a fierce loyalty to their new homeland. Nevertheless, both world wars took a toll on their communities. About six million Germans came to America in the 1800s and up to the early 1900’s. The United States had 76.3 million people in total at the change of the century. Many of those immigrants were still German-speaking in addition to English-speaking and to varying degrees, unassimilated. That made them a target even before conflict in Europe began. But war in Europe brought divisions in America to the forefront. President Wilson was pointed in his verbal attacks on “hyphenated Americans” (such as German-Americans), questioning their loyalty and inciting both modest and extreme acts of violence.

Many German news publications were run out of business by a bolstered vitriol washing across the country. German street names were changed. Some schools named after Germans were rechristened, and many Germans voluntarily changed business and even personal names to better fit in.

Many families who had emigrated one or two generations earlier from Germany had members among the first to stand up for service in both wars. However, they were not always rewarded for their patriotism by fellow Americans. A great deal of violence and ostracism took place against German-Americans.

As a group, however, German immigrants fared significantly better than Japanese-ancestry American citizens. Many Japanese immigrants were taken to concentration camps during the Second World War. While they were far different from the concentration camps of the Nazis in Germany, they were still an extreme violation of civil rights and cost those families many financial harms and personal distress. Like the Germans, almost all of the Japanese immigrants were fiercely loyal to the United States.

Emigrants shared a lavatory and cooking area.

Each car had berths for sleeping.