South Dakota; A land of weather extremes

BLIZZARDS AND CYCLONES UNLIKE WEATHER EUROPEANS HAD EVER KNOWN

Second photograph of a “cyclone” in 1884

The second photograph in history of a tornado was taken within 50 miles of Mt. Vernon near Howard, Miner County, Dakotas, on August 28, 1884. And what a photo it was.

The central twister is dark black and forboding, but is accompanied by two smaller funnels. Known as a multiple vortex, reports indicate the two were just receding into the marvelous thunderstorm above. The photograph was taken by F. N. Robinson from a street in the town of Howard. The photograph is well known and the plate resides with the South Dakota State Historical society as well as prints from the time period.

Robinson took a total of four plates after assembling his photographic equipment. The tornadoes were visible for a long period of time from Howard - Robinson said two hours, which seems an unrealistically long estimate. The tornado approached Howard directly, then passed just to one side. The first plate, taken immediately before the one shown, offers a pair of tornadoes, both touching the ground. Robinson made multiple souvenir postcards of the second plate.

A photograph of a tornado and two funnel clouds, taken on Thursday, August 28, 1884 by photographer F.N. Robinson of Howard is on display in the research room of the South Dakota State Historical Society-Archives at the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre.

From the main street of Garnett, KS, a funnel was photographed April 26th, 1884 by A.A. Adams.

The actual first photograph of a weaker but rope-like funnel angling at 45 degrees was taken from the main street in Garnett, KS, on April 26th of the same year as the Robinson photographs on August 28th, 1884. His claim to having the first photograph was likely based on a lack of knowledge of the other photograph.

Homesteaders were beginning to understand just how erratic the weather in the Great Plains States could be. Many had been sent back to eastern states in defeat. The art of photography saved a few examples of cyclones, blizzards, droughts and floods as evidence of their struggle.

Later research of the Robinson storm of Howard, SD, showed two adjacent cells in the same storm front produced four separate funnels.

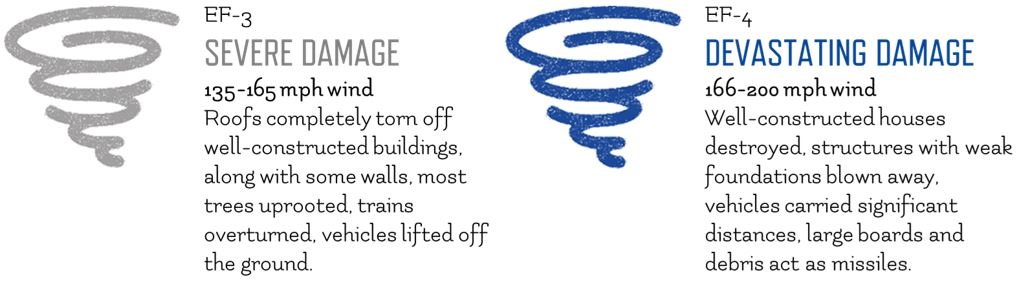

Each reached the ground, and each was an F3 or F4 which are “severe” and “devastating,” respectively. Although the Fujita Scale for measuring the damage of tornadoes was not developed until the 1960s, if descriptions exist of damage done, particularly if there is also photographic evidence, the scale can be applied. In the August 1884 case of the multiple tornadoes, both are available.

The stereo camera pictured was made between 1885 and 1890, and would likely be similar to the one used for the Garnett, KS, tornado photograph of 1884. CREDIT

One of the four tracks as determined and mapped in 1984 by John T. Snow, Department of Geosciences, Purdue University, touches the northeast corner of Davison County, which includes Mt. Vernon. Four or six persons died and others were injured. The advent of the storm cellar was not far away as farmers faced the wrath of “tornado alley.”

According to the Snow report published in 1984, the 100th anniversary year of the original Robinson photos. Snow said that, “Property damage and loss of livestock was extensive, particularly along the James River.”

“The events of 28 August 1884 left lasting impressions on the people involved. S. D. Flora, investigating these storms in the early 1950s, obtained several vivid accounts from observers still living at that time.”

- John T. Snow, Purdue University

The Great Plains, a high plateau of semi-arid grassland. Once the bottom of a shallow sea during the Cretaceous Period, its soils covered limestone laid down 100 million years before, and were held together by the roots of grasses and wildflowers penetrating as far as 16 feet below the surface. Plowing unraveled that ecosystem.

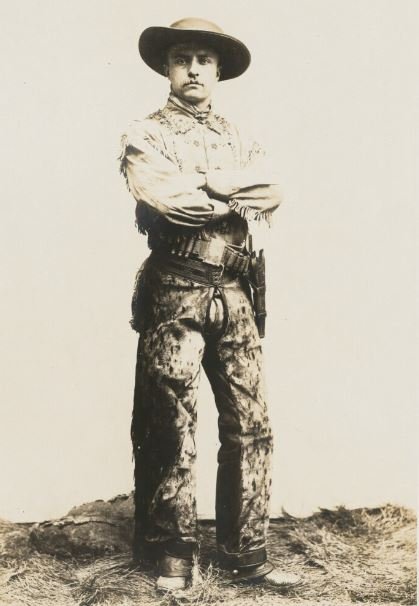

The Great Plains weather thwarted even the dreams of Theodore Roosevelt in 1886-1887

In 1886, a lengthy drought in summer was followed by devilish, extraordinary winter storms. One after another. Livestock were devastated. Hardier cattle survived the worst of the storms long enough to eat the tar paper off houses in Medora, Dakota Territory, before collapsing in that outpost. Snow drifts were so tremendous, other cattle were found dead high in in trees after the snow melted the following late spring. The starving cattle had resorted to eating twigs from tree tops the drifts had buried before dying over the branches which caught their carcasses during the thaw.

Such extremes, which were not exceptions but the rule, caused even future President Theodore Roosevelt to have second thoughts about his Elkhorn Ranch north of Medora, DT, and his Maltese Cross Ranch to the south. The man who would storm San Juan Hill and was known for getting over any physical obstacle in his path was astonished. Roosevelt had lost 60% of his livestock in the 1886-87 fall through spring storms. Uncharacteristically, he summed up the ferocity of nature and decided to give up on the ranch. He returned to a life in New York with the childhood sweetheart he had recently married, Edith Carow. To a friend, he wrote of the consequences of the weather on his dreams:

“Well, we have had a perfect smashup all through the cattle country of the northwest. The losses are crippling. For the first time I have been utterly unable to enjoy a visit to my ranch. I shall be glad to get home.”

- Theodore Roosevelt, 1887

Theodore Roosevelt as a ranch operator.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch.

The weather of the great plains dealt the operation crippling blows to both the Elkhorn Ranch and his Maltese Cross Ranch further south.

1. Rescue party at Huron, bound together by ropes, searching for missing children

2. A schoolmistress compels a pupil to walk all night to prevent freezing.

3. Another brave teacher shelters one of her pupils from the storm.

1888 Children’s Blizzard

19 years before the Links arrived in Mt. Vernon in their emigrant (railroad) car, and a year before South Dakota became a state, one of the most unusual and disasterous weather events in the history of a young country occurred.

The meteorological disaster was far from an isolated event. Weather on the Great Plains was generally quick to change, difficult for a fledgling and ill-equipped weather service to predict, and could be extreme in any season. And often, it was. Buildings, crops and livestock proved no match for the weather.

Called the Schoolhouse Blizzard, or the Children’s Blizzard, that storm ripped out of Montana on January 12, 1888 headed for several plains states. The event was caused by the a tremendous Arctic cold front running into a huge body of warm, moisture-laden air coming north from the Gulf of Mexico.

The weather in front of the fast-moving storm was surprisingly warm, promising a wonderful day in the upper 60s. Many children throughout the Dakotas (north and south were not yet split), Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas left their jackets, gloves and scarves at home expecting encouraging weather all day after weeks of bitter cold.

The storm being pushed under the warm, moist envelope coming far north of its normal winter boundaries - in what might today be called a “cyclone bomb” - gained tremendous moisture resources as it absorbed an extreme influx of energy. The deadly result across a huge swath cut out of the midsection, was a drop of nearly 100 degrees in less than 24 hours. Along its leading edge, the front dropped temperatures that were near the 70s down to below freezing in literally minutes.

The “snow,” due to this unusual storm, was not of normal structure, but instead made up of super-fine ice crystals. The cruel fine “diamond dust” gagged people, quickly eliminated their ability to see, and sifted through clothing and melted upon contact with skin underneath. Perhaps most devastating, it caught children under-dressed in schoolhouses that were drafty and with often only a few hours allotment of fuel coal or wood available. In many areas, it caught children in open country on their way home. Farmers caught only yards away from their homes or in barns when the storm rolled across them were unable to return to safety. Thousands of individuals were immediately isolated in unsurvivable conditions.

235 perished on that day. Many of those were school children.

A weather map showing the Children’s, or Schoolhouse, Blizzard front crossing the Great Plains and marked at three critical hours, dropping temperatures nearly 100 degrees. Children in schoolhouses or on their way home from six states or future states were caught in the maelstrom of ice crystals and extreme winds. The stories of heartbreak and miracles of survival were woven into a compelling book by David Laskin published in 2005 titled simply, “The Children’s Blizzard.”

January 12, 1888; Advance of the cold wave

The Schoolhouse Blizzard front crossing the Great Plains and marked at three critical hours, dropping temperatures nearly 100 degrees. Children in schoolhouses or on their way home from six states or future states were caught in the maelstrom of ice crystals and extreme winds. The stories of heartbreak and miracles of survival were woven into a compelling book by David Laskin published in 2005 titled simply, “The Children’s Blizzard.”

An unforgiving land continues to generate threats after the Links build their home

Literally thousands of families now struggled against nature across the American mid-section, supported in most cases by rail lines, but with slight other infrastructure.

Many were in the same position as the Link family. They had struggled on the Great Plains, had accomplished much and in some years could produce good crops. In many cases, water had to be hauled during drought, and in others an aquifer was struck. In some places, like South Dakota, winters often were too harsh for limited resources available to keep livestock alive. In some, flooding and stunning storms took crops nearly ready for harvest.

All in all, according to Edna Link, who experienced such natural phenomena, the weather became an increasing drawback to farming in South Dakota. That fact perhaps added to Charles’ unsatiated quest for the perfect location to farm. Elsewhere. Soon he longed for better weather. Warmer in winter and calmer in summer. Clara supported that desire dispite all the toil that beginning their lives over had required.