PUTTING FOOD ON THE TABLE WHEN FARMING FAILS

New Mexico Chapter 4

INTRO EUROPE GERMANY OHIO INDIANA SOUTH DAKOTA NEW MEXICO KANSAS DEEPER LOOKS BOOK

A new town replete with great promise

Some of the businesses functioning in town when the Links arrived were equivalents to those in many other just-established towns scattered every seven to ten miles along railways connecting the nation:

G. Berlin General Store and Grocery

Campbell Merchandise

Foxworth and Gilbraith Lumber Company

Schneider Bank

Obar Progress (Newspaper)

Peal Billiards Hall

Greaser Meats

H.P. White Nickel Store

Jones and Cheever Grain and Seed

The Obar Blacksmith

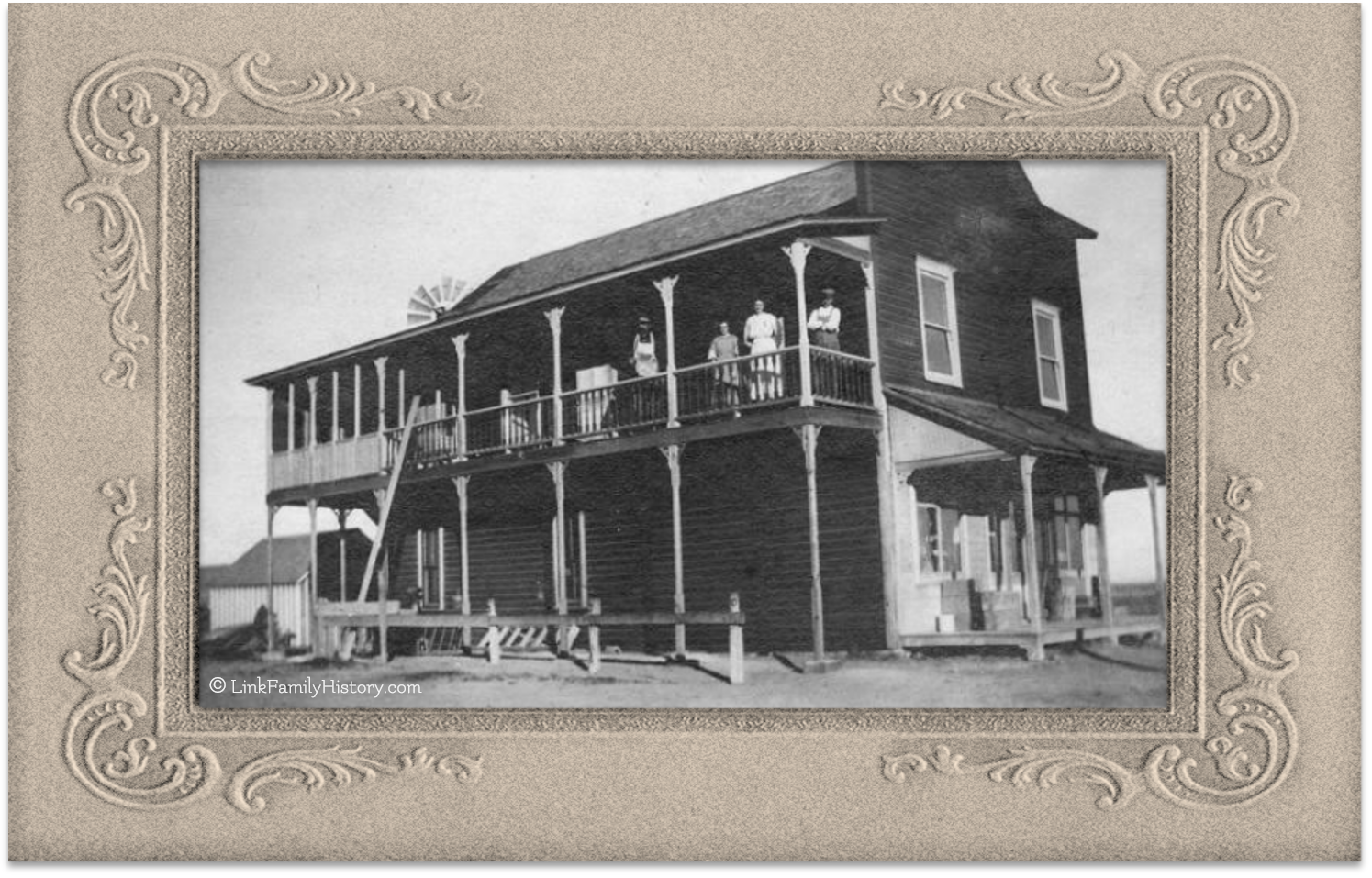

The Wylie Hotel

Perry Investments Company

Schneider Real Estate

Perry and Robinson Real Estate

Elden Link at G. Berlin’s merchandise store in Obar, NM.

Obar school block type. The school was two stories with nine windows and a double door across the front elevation. Four matching windows flanked each side.

Obar had a handsome, two story, carved-stone block high school building with large 6-paned windows on both levels and a double-door entryway, according to Edna Link, who was to become a school teacher herself. The school was not a public institution but paid “by the scholar” on a subscription basis. Above each vertical window was a large contrasting limestone lintel which gave the building a very substantial look.

Edna taught grammar school in both Obar and Montoya, NM, (today, another ghost town) on the far side of Tucumcari. As a ghost town, Montoya still has the Richardson Store, which ruins remain.

Edna Link and students in Obar or Montoya.

The New Mexico Land and Immigration Company had an office in the city, but was headquartered in Topeka, KS.

L.L. Klinefelter edited the Obar Progress newspaper and handled all printing required for the citizens out of a small clapboard fronted building. Starting as the Perry Progress, but changing to Obar Progress with the town’s name change in October of 1908, it was published until July 30, 1915, by which time the bottom had generally dropped out of the local economy.

For three more years, the paper was included as part of the Tribune-Progress, published in Glenrio, NM, directly on the border with Texas and to the south-southeast of Obar.

One last effort to make a go of things

The Links enjoyed their surroundings at Obar by most measures from letters of the time.

Although the grand hotel envisioned in the brochures from the New Mexico Land and Immigration Company was not built, the Wylie Hotel was opened. Here, staff or guests line the top balcony. A sleeping porch is well elevated for breezes along the back with a wind-powered water pump behind. The July high in Obar averages 92 degrees with the low in January averaging 23 degrees. The elevation at Obar is 4,130 feet which made for cooler nights in the summer, but its southerly location kept winters from being brutally cold. Something the Link Family was grateful for, at least before it became obvious that crops could not be grown on their homestead.

AI enhanced detail of sleeping porch at Wylie Hotel.

The community was filled with exceptional people who did not shirk from effort, had varied and extensive experience, and posessed the general skills and will to succeed. The hurdles to getting to Obar, planning the homestead, the requirement of farming knowledge being a necessity, all contributed to screening out quitters and the less-skilled. However, like everyone who homesteaded in this area, they faced diminishing crop returns as the natural rain averages fell back within normal ranges. The result was unsustainable.

Homesteaders and the citizens of Obar alike were left to wonder, what can this ground we have purchased with our toil, sweat, money and tears produce?

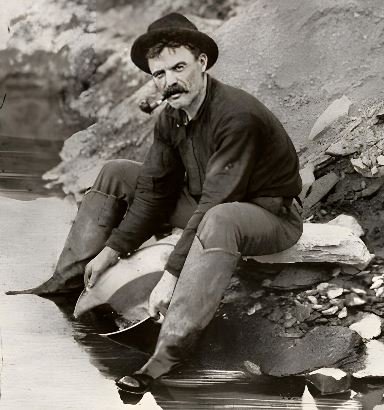

Golden opportunity on rocky peaks

Four years before the Links arrived, there had been news of placer gold deposits found in Quay County, something not unknown in New Mexico.

In fact, thirty-three placer districts in New Mexico are estimated to have produced a minimum of 661,000 ounces of placer gold from 1828 to 1968. On today’s market that would equate to 9.2 million dollars a year. So when the report came through that placer nuggets "the size of wheat grains" had been discovered laying about Revoulto Creek 16 miles to the west of Obar, it must have piqued everyone’s interest. Obar residents on various occasions surely came to a point of wishing some of that gold would turn up where they could access some of it to turn their fortunes, both figuratively and literally.

However, a publication by investigator “Jones” which studied the claim that year for the State of New Mexico concluded “a much-publicized ‘gold strike’ in January 1904 was a hoax. The gravels on Reveulto Creek, 18 miles east of Tucumcari, were salted.”

Quay County, in fact, has never been rich in any normal mineral deposit discovered to date. The New Mexico Bureau of Mines in 1957 summarized this characteristic in a report saying, “No metallic mineral production ever has been reported from this county [Quay]…” However, shortly after the report came out, uranium deposits began to be discovered throughout the bottom three quarters of the county. Even that did not include Obar.

It appeared mineral discoveries were not going to save the farmers from their dilemma of an inability to farm well in most years.

A resource the ground provided,

for which no rain was required

Location of gravel pit that eventually most of the Link family would work at.

The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific discovered, then established a large gravel pit a mile to the north of Obar after finding a “good quality and reliable” source.

Gravel is required between railroad crossties to help keep them in place and as a bed to promote drainage while limiting erosion. Known as ballast, gravel of about 1.5” size forms a bed for crossties, also called sleepers.

Most railroad gravel is granite (igneous rock formed mostly of quartz, feldspar and mica), trap rock (dark, igneous stone) or basalt (dark, fine-grained volcanic rock). However, good quality limestone gravel can also be used where the preferred stones are distant.

Obar sits on a large high plains plateau capped by limestone - called the Ogallala Formation - cemented with other sedimented rocks to create a very hard substance known as caliche or calcrete (calcium concrete).

Caliche layer rock, found as a cap to much of the Ogalalla limestone bench in the Obar area. The very hard rock when crushed is excellent for railroad use.

The limestone in the caliche was laid down when the central section of North America was a shallow sea teeming with life. As that life perished, it built up on the sea floor. The shells and skeletons of the perished sea life formed thick layers of calcium to produce limestone built up over millions of years. However, as a gravel, limestone can be chalky or easy to break. In the case of the Obar region, uplift which formed the Rockies caused rivers to form and through erosion harder rocks to come down from the mountains in glacial and other runoff. When those rocks combined with the cementing properties of the limestone, the very hard caliche layer was formed. Caliche is so hard in fact, that many southwestern homes where the “caliche layer” is common have no basement.

Railroad gravel, even today, is always in demand for repairs and maintenance up and down railway lines. So, the Quay County land did find a small offering to make to the locals trying to survive there.

Forest, Elden and Oscar each worked at the gravel pit, which had the place name of “Gravel Pit” just as if it were a town. The rest of the Links - Charles, Clara and Mary operated a boarding house for workers and visiting railroad officials. Mary was a pre-teen, but certainly would have had duties to help out in this enterprise.

Edna was teaching school with terms in both Obar and Montoya down the line. When she taught at Montoya, she would have roomed there.

After a few years it became obvious that Obar was not going to be a growing concern and the gravel pit work was unrewarding. The family, and others, would have known a generous profit was not likely to be made from their homesteads. The land might not be salable for the cost of the buildings place on the claims. So the family got out, starting with the eldest child, Forest.

Charles, Clara, Edna, Elden and Mary stayed until 1913 - long enough to give them full title to their homestead they had “proved up” five years after the application.