FOUNDATIONS FLEETING IN TIME

New Mexico Chapter 5

INTRO EUROPE GERMANY OHIO INDIANA SOUTH DAKOTA NEW MEXICO KANSAS DEEPER LOOKS BOOK

Marker for Obar contributed by the G. Berlin family and constructed in the mid-1970s when foundations could still be seen in the background. The marker is on Highway 54 7.7 miles southwest of Nara Visa and 40.9 miles northeast of Tucumcari.

From the U.S. Highway 54 marker when the plaque was nearly new in the late 1970s. Today the marker is tarnished and much of the base covered with gravel. However, it still offers a visual pause to remind of a bygone era. Most of the foundation ruins pictured are now gone.

Ruins of Obar building foundation. 1977. Today, most of the remaining fragments were gone.

MANY FAMILIES, MANY OUTCOMES

“The graveyard of failures is full of the monuments erected over the blasted hopes of men who didn’t know a good thing when they say it.”

- New Mexico Land and Immigration Company, 1908

Obar’s editor and printer, L.L. Klinefelter, died in 1915 at which time the Obar Progress was closed for business. He is buried in the Obar Cemetery, one of the few remnants of the ghost town.

The Glenrio, NM, Tribune, also of Quay County, bought the name and carried on local Obar news, such as there was, for three more years to 1918.

The Berlin family, who ran one of two mercantiles, wished to commemorate the townsite. They settled on funding a marker on U.S. Highway 54. The highway had been built past Obar adjacent to the Rock Island line in 1926. The Berlins worked in cooperation with the New Mexico Highway Commission, and a stone marker with bronze plaque was placed in the late 1970s.

Other families had oral and written stories from Obar. They remembered it in countless retellings of tales around dinner tables, on holidays and when traveling through New Mexico.

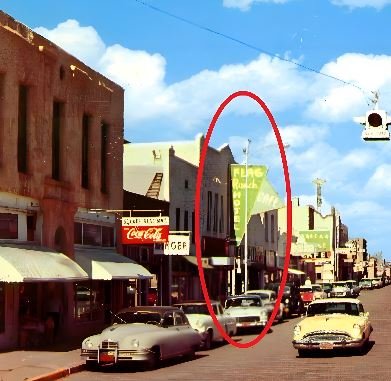

The Greaser family, who ran the butcher shop in Obar, moved away from their Flag Ranch homestead to Tucumcari, NM. 42 miles down the Rock Island line. There they opened the Flag Hotel and Cafe. In 1934, the family revisited the Ranch for a reunion and took a group photo of the pioneers and succeeding generations.

The Link family eventually fulfilled their five years improvement of the claim. Some of the children worked their way up the railroad line as described in the section on Kansas. The rest of the family made it back to South Dakota where they began, again, to farm.

A ranch cow overlooks ruins of a foundation of Obar in 1977.

From Indian lands to ranchlands to townsite with homesteads - then back to ranching country

By 1700, arguably the fiercest of the North American Indian tribes, began to move into what would become Quay County, displacing over time Jicarilla Apache peoples. The Jicarilla Apaches were also a fierce fighting society. Both had mastered use of the horse to expand their areas of influence.

Another band of Apaches, the Chiricahua, was the last tribe to surrender in the long period of British-American colonization of North American. Both Comanche and Apache groups had significant success also against Spainish would-be colonizers who failed to bring about their subjugation.

Pueblo and Navajo communities were also widely distributed across New Mexico. Ultimately, the Jicarilla Apache were defeated by the U.S. Army in 1855, and the Comanche 20 years later. The surrender of Geronimo’s Chiricahua warriors was the formal ending of the American continent Indian Wars in 1886 in southeastern Arizona.

Evidence of Obar is all but gone

It has not been rediscoved for certain if the New Mexico Land and Immigration Company ever completed the Obar Hotel, but it seems very unlikely. A limestone building of that stature would have left remnants for many decades. Another hotel, the Wylie, was a wooden structure, and might have filled the lodging gap for a town that early-on may have suspected it was the victim of a plan going awry.

There were families in the area for many years, and some remain today in ranching, or have at least held on to the land through future generations. 1953 was generally considered “the last year.” Cattle are raised in the vicinity and keep watch over the stones, rusted cutlery, broken pieces of stoneware and disintegrating nails that once held purpose in a town of great promise.

Illustration - Flag Ranch Hotel and Cafe, Tucson.

The Flag Ranch Hotel and Cafe, from a section of a postcard of the late 1950s. That decade was Tucumcari’s “hey day” with a population of about 8,500. Flag Ranch was the Greaser family’s homestead in Obar, NM, where they operated the butcher business.

The Greaser Meat Market supplied Obar residents fresh beef and other meats. The Greaser family returned to visit their Flag Ranch near Obar for a reunion after having moved to Tucumcari where they started the Flag Ranch Hotel and Cafe downtown, pictured left. Circa 1958. CREDIT