A LAND BETTER SUITED FOR RANCHING

New Mexico Chapter 2

INTRO EUROPE GERMANY OHIO INDIANA SOUTH DAKOTA NEW MEXICO KANSAS DEEPER LOOKS BOOK

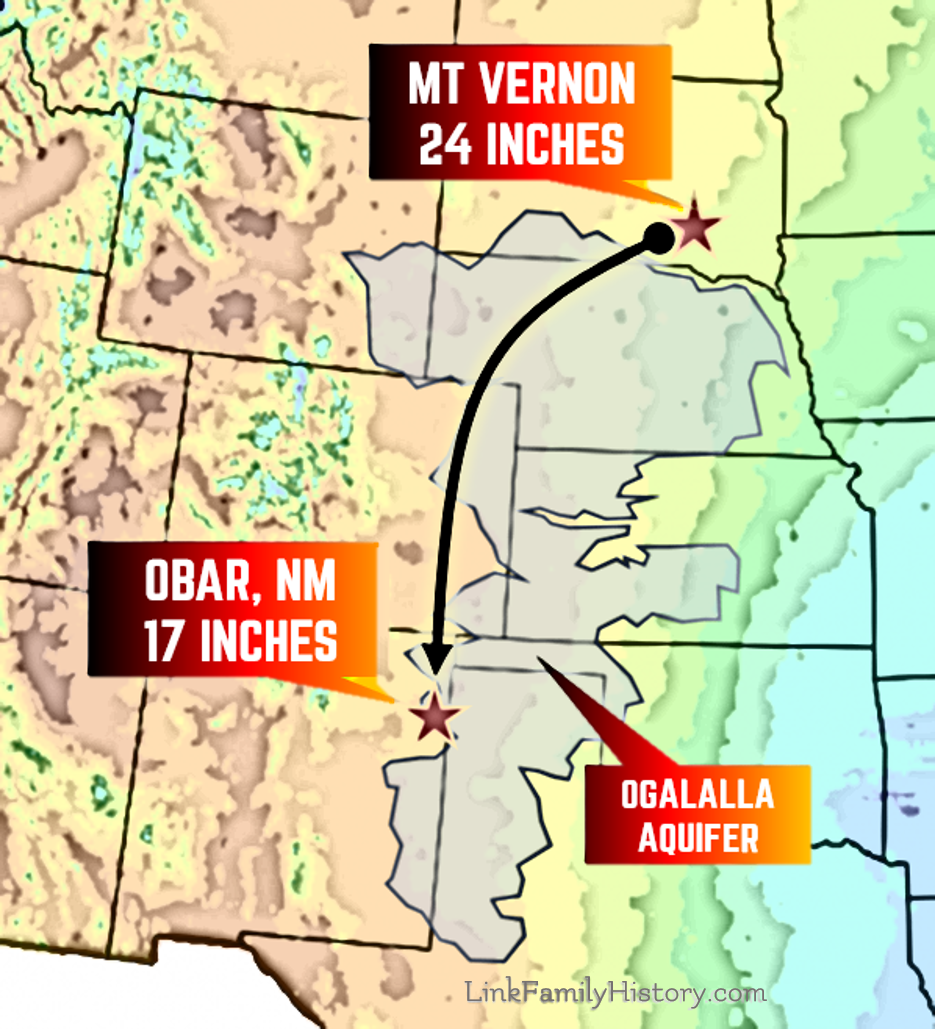

From Mt. Vernon, SD, to Obar, NM, a drop of 7 inches in rainfall (29 percent) per year

Throughout the Southwest, the weather was uncharacteristically wet for most of the decade prior to the establishment of Obar.

About the time many of the original settlers were starting to plow up the grassland to begin farming, droughthy years began to return. Although there were also good rain years up through about 1913.

New residents in the early, wetter than normal years, were impressed by what would grow. Even an orchard of apples was planted near Obar and had provided local merchants with fruit for a time. If mature trees were brought in from the east, that orchard could have just made the tail end of the rainy period. If grown from seed, eight years would have been required for the first harvest, so that seems unlikely.

Nursery-grown trees were more likely used in the orchard. Mt. Hope Nursery of Lawrence, KS, was one of the nearest sources of a huge variety of eastern trees which were shipped by rail to all points west, even including the Pacific states.

SIDEBAR | The original town name of Perry was one of 21 other American towns with post offices carrying that name in early 1908. The early residents were pleased to announce after the moniker change that they were now the only “Obar” post office designation in the world.

Charles supported attempts to grow Obar, but at first was unaware of the shift to lesser rain

It was undoubtedly exciting, as Edna Link reported, to move to a warmer climate after experiencing the variables of South Dakota early fall, long winter and late spring.

The testimony C.U. had gathered in his trips to Obar supported the concept that any number of crops might grow there. There were no climate data pages on the internet at the time or even many in books to consult to show that recent years had been rainfall anomalies. Basically, they were charting the unknown.

Weather prediction was in its infancy and often inaccurate.

The fledgling “Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce” had been begun in 1870 within the Army Signal Corps. Any kind of official weather observations had begun in Santa Fe, NM, only on January 1, 1849. Santa Fe had a very different climate and altitude from Quay County, 251 miles to the east and along the edge of the Great Plains. The Division of Telegrams received a shortened name, “United States Weather Service,” only 18 years old when the Link family stepped off the Rock Island into Obar Station. It struggled to predict weather a day or two in advance at times, although the science had launched.

Still, the information was not only unreliable at times, but could be dangerously misleading. When the Great Hurricane of 1900 was approaching Galveston, TX, in late August of that year, it was drawn on maps produced by the Weather Service. They showed the storm as moving north across Florida and predicted it would run along the East Coast states just out to sea. Meanwhile the storm was actually bearing down on Texas, 900 miles away from where it was drawn on weather charts to be. Just before Galveston was struck by the brunt of the hurricane, the government weather maps still showed the hurricane along the east coast.

At least 6,000, and perhaps as many as 12,000 people died in the Galveston disaster, the worst in terms of deaths American history. Many of those on the island were greatly unaware of the approaching storm on September 8th, the day of landfall over the island. That storm, and the Weather Service’s incredibly inaccurate reports of its location, had occurred just eight years before the Links set foot in Obar.

Galveston Hurricane of 1900 depiction. The Weather Service charted the storm off the East Coast as it was entering Galveston, TX. Library of Congress.

It was a time when reliable weather information, much less long-term climate information, was unavailable at the level needed for decisions on where to farm versus where to ranch.

An excellent book covering both the Weather Service (which later became the United States Weather Bureau), its Galveston chief meterologist Isaac Cline (who warned the storm was probably headed for the city of Galveston from his observations), and which tells the stories of many people who faced the storm, was written by Eric Larson, called Isaac’s Storm.

There were no resources in 1908 that would tell those interested in Quay County, NM, to homestead and farm around that adequate rain was not available on average for any standard crops.

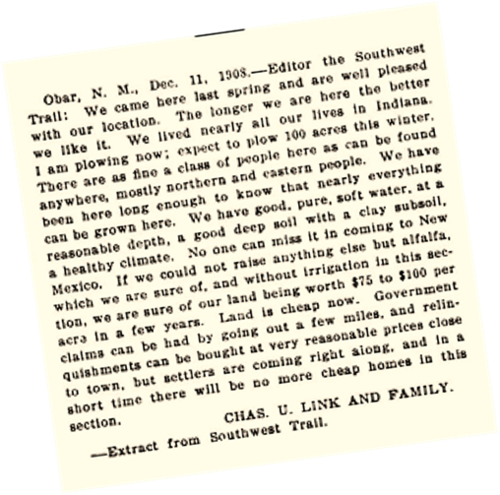

Obar, N.M. December 11, 1908 – To: Editor the Southwest Trail

“We came here last spring and are well pleased with our location.“The longer we are here the better we like it. We lived nearly all our lives in Indiana. I am plowing now; expect to plow 100 acres this winter. There are as fine a class of people here as can be found anywhere, mostly northern and eastern people. We have been here long enough to know that nearly everything can be grown here. We have good, pure, soft water, at a reasonable depth, a good deep soil with a clay subsoil, a healthy climate.

“No one can miss it in coming to New Mexico. If we could not raise anything else but alfalfa, which we are sure of, and without irrigation in this section, we are sure of our land being worth $75 to $100 per acre in a few years.

“Land is cheap now. Government clams can be had by going out a few miles, and relinquishments can be bought at very reasonable prices close to town, but settlers are coming right along, and in a short time there will be no more cheap homes in this section.”

- Charles Ulysses Link and Family

That Quay County received only 17 inches of rain a year would not have been generally known, as data was not sufficient

It was known, however, that even alfalfa - a low-moisture, drought-tolerant crop - required (on the dry side) about 18 inches a year to grow, with some sources citing more. Rainfall requirements for various crops depended on variables such as the months the rain usually began, when temperatures were right for planting, the frequency of rains and general soil characteristics such as moisture retention. Because the roots of alfalfa go down 20 feet, it was considered a fall-back crop capable of meeting the toughest climate the plains could dish out. Many families would come to find a new perspective on that matter.

The handwriting on this exaggeration postcard says “Raised around Obar by C.U. Link.” The genre was popular in the early 1900s up until German-made postcards were banned during World War II. The card was postmarked 1913 by the Obar post office and sent to Forest E. Link in Pratt, Kansas.

The Ogallala Aquifer was originally beneath all of Quay County. Today, it has been drained in the central and southwestern parts of the county and is unreachable. In 1908, however, ground water - found “at reasonable depths” according to Charles - could have, and probably was used to irrigate. Such an effort would have been attempted as the depth of the deficiency in rain began to be realized.

A native form of vegetation that did grow in the county and was later cultivated as a last resort was soaptree yucca, or yucca elata. Today it is the state flower of New Mexico. Boxcar loads were gathered and shipped to urban centers to the east on the Rock Island, particularly St. Louis. The young flower stocks can be used as cattle feed and the roots and trunks can be used to produce a soap substitute. Although off to a good start originally, demand dwindled after a few seasons.

To help his community, and his chances of increasing land prices, C.U. Link allowed his home and barn to be photographed and placed in new NML&IC enticements. Each prospectus was creative and compelling during a time when many believed in the theory that “rainfall follows the plow.” In other words, that opening up the prairie led to more rain above that prairie.

In fact, the opposite proved to be the case. Opening up the soil with plows and cutting off the natural grasses and plants that held the plains together with incredibly long roots led to desiccation of the soil. Freed soil exposed to drought that was common went flying during frequent windstorms creating the dust bowl era of the 1930s. Locust plagues were enlarged by farmers bumping up against their habitats with feasts waiting to be consumed. 1856-57, 1874, and 1873 to 1877 generally involved large locust outbreaks. Locusts are simply varieties of short-horned grasshoppers that, under certain conditions, are triggered to multiply and travel in vast hordes to consume plants and leaves. The particularly damaging Rocky Mountain locust became extinct during the early 1900s.

The last homesteads in “the contiguous 48”

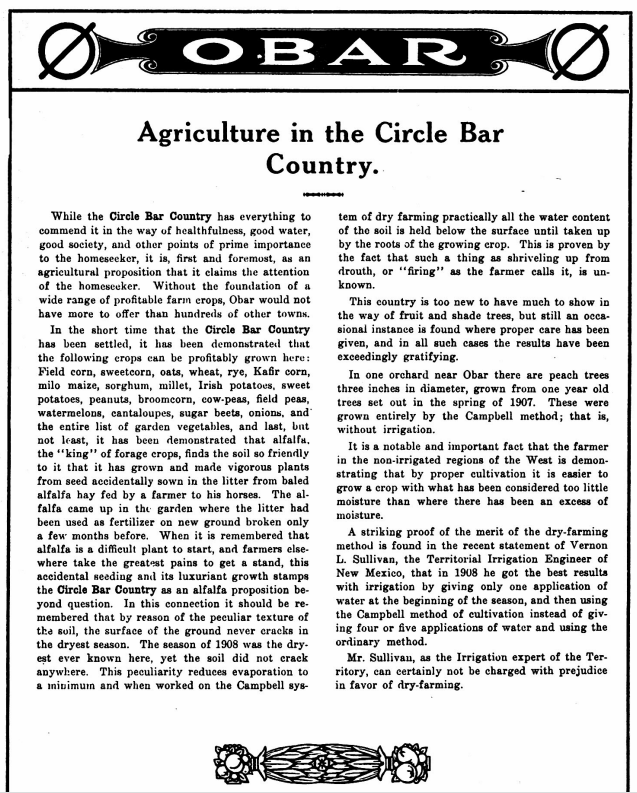

Although the town of Obar involved the significant hurdle of starting a city where there was no river, it also involved attracting homesteaders to surround the town with an essential agriculture base.

Appeals to lot buyers and homesteaders were intermingled by the New Mexico Land and Immigration Company.

"A trip across the beautiful prairie, with its waving corn, alfalfa and cotton bloom, is like the realization of a cherished dream of a new home in the West. It matters not from what part of the Union you come, you will find here, growing in tropical luxuriance, the fruits and flowers to which you have become accustomed in the old home...

‘If you are looking for a new home and want to better your condition, come to Obar, the land of sunshine, where with the least encouragement the flowers bloom and the crops grow abundantly. '“The man from the rugged coast of Maine, and the man from the sunset slope of the Pacific, the thrifty Yankee and the hospitable Southerner, here meet and mingle on a common level. Here you will be estimated at your true value...

"New Mexico needs you to help develop her wonderful resources... Come to a new town in a magnificent new country, and do not be delayed by skepticism."