AGRARIANS & THE GILDED AGE

Indiana Chapter 7

INTRO EUROPE GERMANY OHIO INDIANA SOUTH DAKOTA NEW MEXICO KANSAS DEEPER LOOKS BOOK

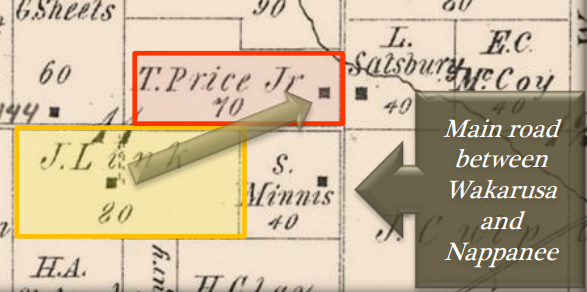

With Nappanee to the south and Wakarusa to the north, the 80 acres farmed by the Jacob Link family were well situated.

The Gilded Age left farmers behind

Farming conditions in the last three decades of the 1800s were tough on American farmers.

Between 1870 and 1897 wheat prices fell from $106 per 100 bushels to $63. Corn similarly fell from $43 to $29 (U.S. Economic History, Gale). The “McKinley Tariff” of 1890 increased average duties across all imports from 38% to 49.5%. While the tariff was intended to help farmers, it added greatly to their costs for supplies.

Corporation owners benefited the most from such tariffs. Those owners of those corporations were know during the Gilded Age - 1877 to 1900 - as “captains of industry.” It could be either a term of favor or of disfavor depending on the politics of the speaker. In 1870, citizens involved in agriculture accounted for half the United States’ population, so those farmers represented a huge voting bloc. So as farming became less profitable, a significant percentage of Americans were deeply challenged in an industry that had formerly been gainful.

60% of all who tried homesteading

in the late 1800s failed.- Grit

Farmers sought improvement through organization to increase the power of their voices. There were three main efforts to unite farmers into a voting bloc: the Grange, the Farmers' Alliance, and the Populist Party. The Populists looked outside farmers for members as well.

Those unifying responses to decreasing income and increasing production costs were known together as the Agrarian Protest Movement.

Farming was still the backbone of the American economy. Issues important to agrarians were more politically significant than today, where farming involves less than two percent of the population. The issue was so important that the 1896 presidential bid of William Jennings Bryan was based on the Populist Party platform designed to correct problems inside the farming economy. Although William McKinley won that election, his support of the gold standard as opposed to the various regulatory approaches supported by the Agrarian Movement actually helped alleviate the agrarians in the long run. The first two decades of the 1900's saw a return of profit to farming families.

The new Link farm.

The Link farm provided sustenance and profit for the three generations living there until the later stages of the Gilded Age.

Elizabeth (Fishel) Link died May 4, 1893 at age 64. Jacob died of a heart attack after the evening meal September 27, 1897 in his 73rd year. Their passings created challenges just before the fortunes of farming began to improve.

The Link children, Elden, Edna, Oscar and baby Mary. Forest was not in this picture, however, would have been the eldest.

With the original generation’s loss, it was decided the Link farm would be sold. An 1874 plat of Locke Township shows the farm contained 80 acres. It is likely the proceeds of the sale were allocated amongst the next generation. C.U. used his share to buy a 50-acre farm along the main road between Wakarusa and Nappanee. So right at the most difficult time for the farming economy, based on three decades of dropping profitability, Charles was starting over.

The new Link farm included an apple orchard. It was decided that corn would be the main crop grown. A community barn-raising on the site took place. In Mennonite and Amish communities, those events were often large and supported by many persons from other farms in the area. Edna recalled those days as "happy times for the Links and their neighbors," even with economic challenges that probably affected her father’s thoughts in the quiet hours.

In a stark change of events, however, the new farm was surrendered to creditors, sometime between 1902 and 1904. The reasons could have been due to the economy or starting over. Perhaps there was a crop failure or funds to build new buildings overextended resources. For whatever reason, or combination of reasons, the Link family found themselves moved to Nappanee where Charles at first rented a home.

The family began its first city lifestyle on the North American continent. Forest Elmer Link was the eldest of the Link children.

One of six born to Charles and Clara, Forest was a Mennonite until the family moved to Nappanee in about 1904. He was 13.

In Nappanee, Forest attended the Methodist Church, the church of his mother's Berkey family. Perhaps Clara decided to return to the church she knew best and he, being older than the other children, was allowed to attend with her. However, his siblings and father attended the Nappanee Mennonite Church where Charles was already back to being heavily involved with music and singing as “chorister.” The family was universally Republican in their thinking as the children became old enough to have political affilliations.

For income, Charles represented a purveyor of farm machinery. His name was listed in advertising placed in local newspapers. Sometime within that first year of recovery in the rental home, C.U. began working on another plan for the family. The next changes for the Links would eventually take them to other parts of the country. As his parents and grandparents before him had chosen, that would mean farther west.