A VIGOROUS, RURAL LIFESTYLE

Indiana Chapter 3

INTRO EUROPE GERMANY OHIO INDIANA SOUTH DAKOTA NEW MEXICO KANSAS DEEPER LOOKS BOOK

Barely discernable at the top of a 1907 photo of the Bauer Brother’s sign, in downtown Wakarusa, are the words “Studebaker Wagons.” The wagon pictured below the sign is a Studebaker product and one that would have been built in South Bend, Indiana. The Studebaker family also emigrated from Germany, and simplified their name from Stutenbecker. Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Company had been founded by brothers Henry and Clement in in 1852. CREDIT

The rural, challenging and lively aura of 1800s Elkhart County

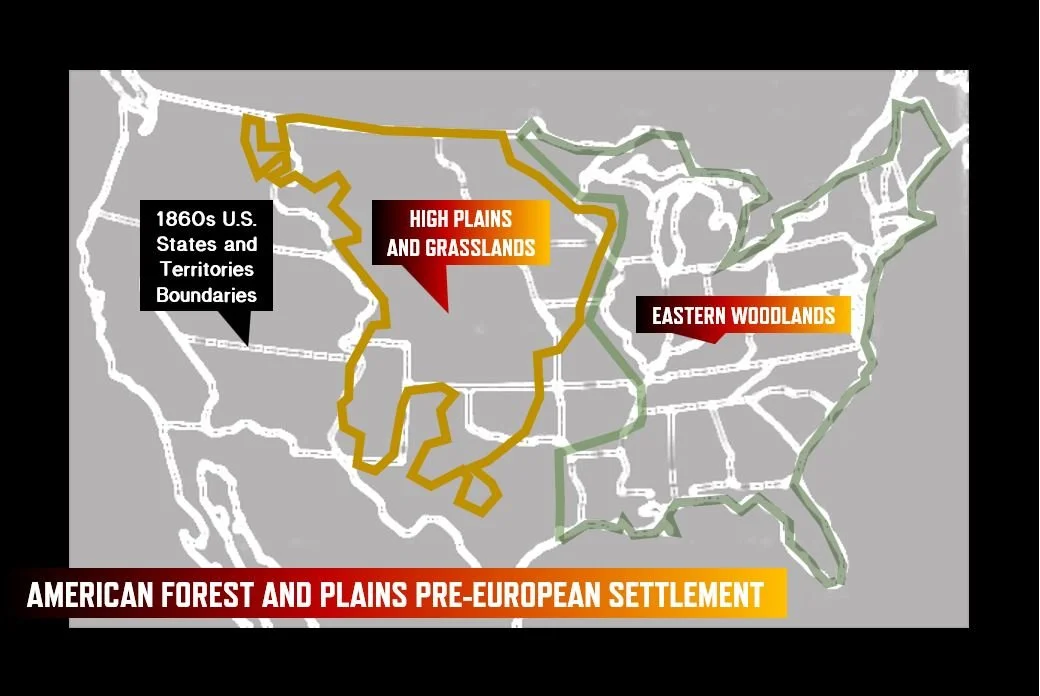

Elkhart farmland was being cut from forest. A frontier then, known as the Midwest today. One of the world’s largest forests, the Eastern Woodlands was being cut down on land that was flat enough to plow and produce crops. It was happening with breathtaking speed all across that imaginary line running between what was better known and what was “the future.”

It greeted immigrants at the Eastern Seaboard and continued to the banks of the Mississippi. The Eastern Woodlands was an indigenous forest of nearly unimaginable proportions. Like the vast and hard to fathom prairie that spread from its western edges to the Rocky Mountains, it seemed nearly endless.

The Link’s farm, on an 80-acre expanse, was close to town, but not so close a wagon ride was not customary for the “trip in” for trading or to attend church.

The approximate Eastern Woodlands extent prior to European settlement. While thinned considerably in its original location to make way for towns and farms, many trees from that forest were transported to towns being formed on the prairies. After a few decades, the trees had begun to spread from towns to surrounding areas creating new forest-covered areas. In glaciated regions, where hilltops and slopes were generally not farmed, the expanded treelines remain into the 21st century. That forest expansion generally ends at about the 98th Meridian where rainfall is too sparse on average to support eastern varieties not in riparian areas or artificially watered.

When Charles Ulysses Link was 11, it was 1880. Charles was recorded in the census information for that year along with sister Margaret, also at home. He would have little or perhaps no personal memory of the sad times in 1872 when three of his siblings died.

Mennonite children, as well as most others on farms from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River, had responsibilities very early in their lives. Their work would include feeding small animals, cleaning, assisting with preparing food or helping with the actual farming. The farming skills required to survive were taught starting early, and children were an integral part of the active farming life by the time they were in their teenage years.

Druggists, a mercantile operator, the harness and buggy purveyors and others front their buildings on South Main in Wakarusa for a photograph.

Vibrant towns were focal points of American economic activity and driven by a rural engine

In 1881, nearby Wakarusa, IN, had 400 citizens. Already, there were two wagon and carriage factories, two harness shops, two drug stores, two dry good stores, one hardware and implement store, one furniture store, one grist mill, two blacksmith shops, one meat market, one hotel, one millinery store, one barber shop, one saloon, two physicians, and one veterinary surgeon. (From History of Elkhart County, 1881).

Cora Chupp, a niece of Charles, came to live with the Links when her mother, Anna Mary (Link) Chupp died not far away in 1872 of consumption. Cora became Charles' closest friend for many childhood years. Charles and Cora were close in age and attended Longstreet School together. They were both active in Holdeman Church enterprises. Cora later married and became Cora Clouse. Cora’s father, Levi, eventually went on to marry again and moved two counties to the west seeking opportunity there.

Charles Ulysses Link at age 19. AI enhanced photograph.

The family's Mennonite faith was an integral part of Charles' daily life. Even with church and farming undertakings, there was still room for many other activities and the excitement of city goings on.

Charles played the clarinet and for a time led the Wakarusa Band. He wrote hymns, at least three of which were published. His son, Forest, would later take up the clarinet and play in several civic bands over time. Charles was chorister at Holdeman Mennonite Church for many years. Some of the music for hymns he wrote were published in hymnals of the day. He also taught at singing schools locally.

Family activities were set up on schedules everyone anticipated. Saturday evenings, the family went to Wakarusa to do a week's worth of trading. Saturday night baths and Sunday school preparation were next on the list before the family members settled into their beds.

The first meal of each day was preceded by Bible reading and prayer. Charles’ daughter, Edna Link (Jones), recalled that, "On Sunday mornings the family drove four miles to a country church (Holdeman Mennonite) rain or shine.

“Father (Charles) was Sunday school superintendent and chorister for singing. There was no organ, but folks did sing."

- Edna Link (Jones)

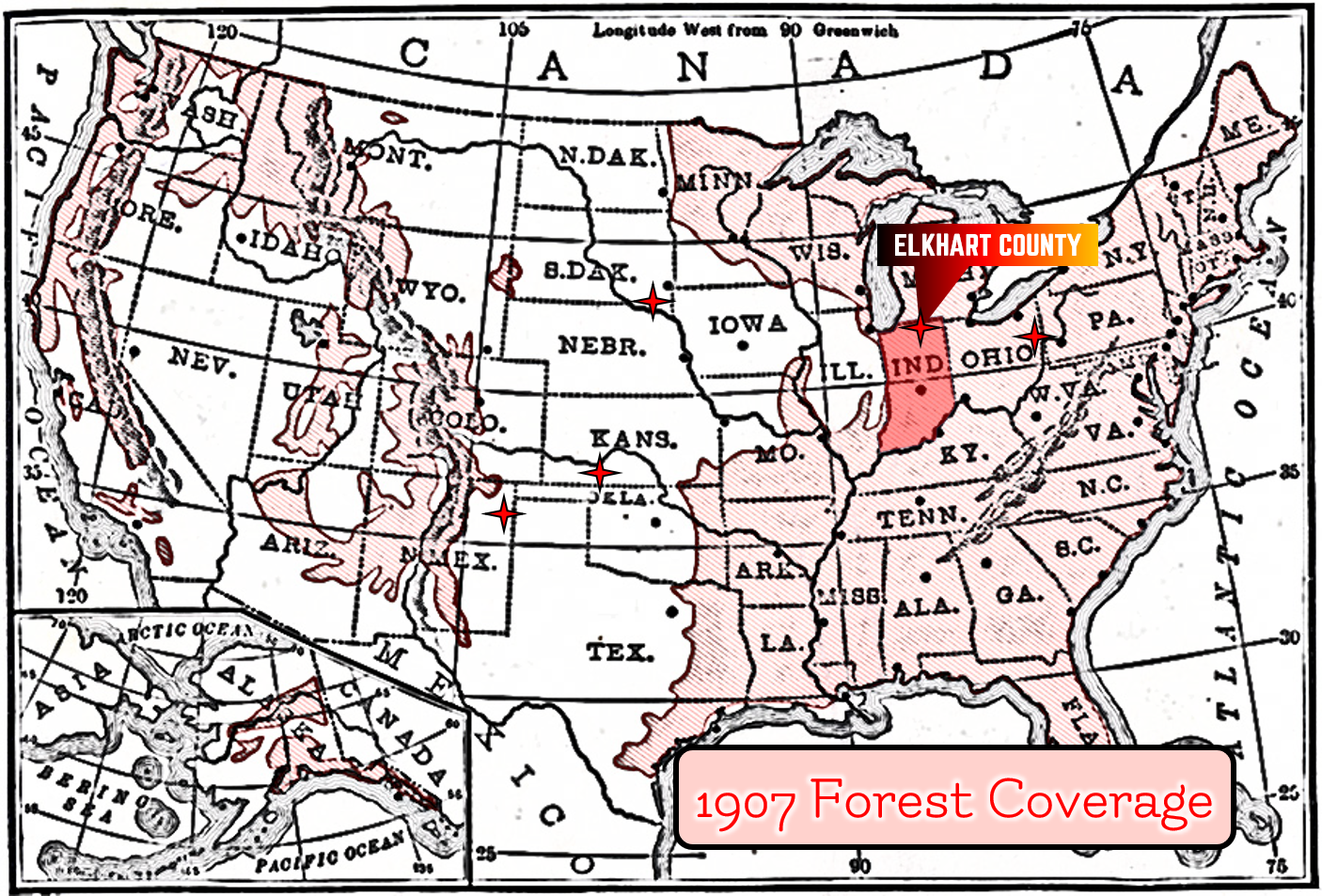

Eastern Woodlands coverage, 1907, and other western forests. Star icons represent places the Link family lived.

The disappearing woodlands

The late 1800s farming and the timber industries would deforest much of the woodlands that had covered Elkhart County.

In some areas of the frontier, such as in eastern Kansas, tallgrass-covered hills left behind by glaciers became covered with trees after city dwellers transplanted their favorite eastern varieties along streets and boulevards. From there, they spread to the unfarmed hills and hillsides.

Past the 100th meridian, what became known as the Great American Desert began. Rainfall to the west of that general reference point was too limited to offer trees outside riparian coridors the opportunity to survive. Early “houses” for homesteaders were often built from sod blocks until lumber could be transported to the prairies by steamboat and wagon. Trains began playing a part in the 1870s as spur lines connected cities formerly accessible only by horse-power or walking. Lacking timber, some homes and many courthouses were built with limestone blocks, the left-behind remains of an inland sea that once overed the central portion of the continent.

Fences were also, in many areas of the Flint Hills of Kansas and westward, made from carved limestone strung with barbed wire made in factories in towns such as Lawrence, KS. Barbed wire, invented in 1867, helped carve up the prairie into individual claims and made cattle drives from Texas and New Mexico to the rail heads in Kansas more difficlut. Difficult enough that limited “wars” broke out between drovers and farmers. Lawmen such as Wyatt Earp (Wichita and Dodge City, KS) and William “Wild Bill” Hickock (Abilene, KS) were chosen specifically to respond to such conflicts, acting on the side of local citizens and farmers. CREDIT

Jacob Link and Jacob Beutler build a new Holdeman meetinghouse in 1875

2001, 150th Anniversary Celebration Program, Holdeman Mennonite Church, Wakarusa, IN.

“The Holdeman founders came into Elkhart County and found it a rich but challenging environment. Timber including very large ash, oak, maple, hickory, walnut, tulip-poplar and beech had to be cleared for each farming area. Sawmills were few, but much of the board-footage cleared was put to use building. Seventeen charter members met, probably in the home of George Holdeman, and set about building a log structure about 24 feet by 34 feet. Of the original members, 14 belonged to the Holdeman family. Members were considered part of the Yellow Creek ministry nearby. The [first] meetinghouse was completed in 1851.

“Just over one acre was purchased across the road from the log meeting house west of Wakarusa and platted for a new church building and cemetery. Later, the cemetery was relocated to North Union Cemetery [where Jacob, Elizabeth and the three children who died during 1872 are buried].”

After plans for a new church building were completed in 1974, the old structure was taken down pieceby-piece and reconstructed on another site by another Mennonite group where it continues to serve as a house of God today.

“In 1875, funds were sufficient to build a frame meetinghouse. The head carpenter was Jacob Link, assisted by Jacob Beutler. Cost of the original construction was $400.50. Several renovations and enlargements were made to the meetinghouse, which served for 99 years.”