Southwest Arizona Riparian Features

Mesquite Bosque

SMALL FOREST

Bosque canopy made up of mesquite trees near Tumacacori Mission.

NPS Photo

Mesquite bosques are happiest around desert rivers where they can find water most of the year. The velvet mesquite is a common Southern Arizona tree that has a dark high-relief bark and its branches spread out low. That feature creates an interesting canopy when many mesquite form a “small forest,” known as a bosque. The tree is a plant found in woodlands of the Sonoran Desert, usually along washes or rivers, and are home to many insects, birds, and even mammals. Bark scorpions, the most venomous of North American species, are common to the Sonoran, and said to favor these trees.

La Pimeria Alta area of the United States and Mexico.

From the National Park Service:

“Today, the mesquite bosque of Tumacacori [Mission along the Santa Cruz south of Tucson] protects the threatened yellow-billed cuckoo and other rare species. It provided the O’odham, and later the Spanish, with wood, medicine, and food.

Mesquite flowers provide important pollen and nectar for wildlife. The flowers are crowded into long spikes called catkins. When fertilized, the flowers form long green fruits that resemble string beans. They grow and mature through the summer, turning tan or streaked with red.

The beans can be eaten at all stages of their growth. The O'odham ate them as a vegetable when green, and ground the pods into a sweet, nutty flour when ripe. They are favored by many animals, including hares, pocket mice, kangaroo rats, pack rats, and javelinas.

Although honey mesquite can be found in the region, the velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina) dominates the landscape of Tumacácori. Some theorize that the Spanish introduction of cattle accelerated the spread of mesquite bosques in the Pimería Alta.”

Cienega

WETLAND SYSTEM

Cienega Corridor, Pima County

Pima County Cienega Corridor Management Plan

A ciénega, sometimes spelled with an “a” in place of the second “e,” is a wetland system unique to the American Southwest. Ciénagas are wet meadows of freshwater, always saturated on much of the surface by ground sources. They may cover the entire basin of a valley and are relatively flat. Between the Southwestern Arizona “archipelago” mountain chains, there are locations where aquifers and springs may support other drainage into the ciénaga. In modern times, much of the wetland is depressed between banks of a few feet.

Las Cienegas National Conservation Area, BLM

From Wikipedia:

“Ciénagas are usually associated with seeps or springs, found in canyon headwaters or along margins of streams. Ciénagas often occur because the geomorphology forces water to the surface, over large areas, not merely through a single pool or channel. In a healthy ciénaga, water slowly migrates through long, wide-scale mats of thick, sponge-like wetland sod.

Ciénaga soils are squishy, permanently saturated, highly organic, black in color or anaerobic. Highly adapted sedges, rushes and reeds are the dominant plants, with succession plants—Goodding's willow, Fremont cottonwoods and scattered Arizona walnuts—found on drier margins, down-valley in healthy ciénagas where water goes underground or along the banks of incised ciénagas.

Ciénagas are not considered true swamps due to their lack of trees, which will drown in historic ciénagas. However, trees do grow in many damaged or drained ciénagas, making the distinction less clear.”

Riparian Zone

INTERFACE BETWEEN LAND AND RIVER

The Santa Cruz River runs through Tumacacori National Historical Park.

NPS Photo

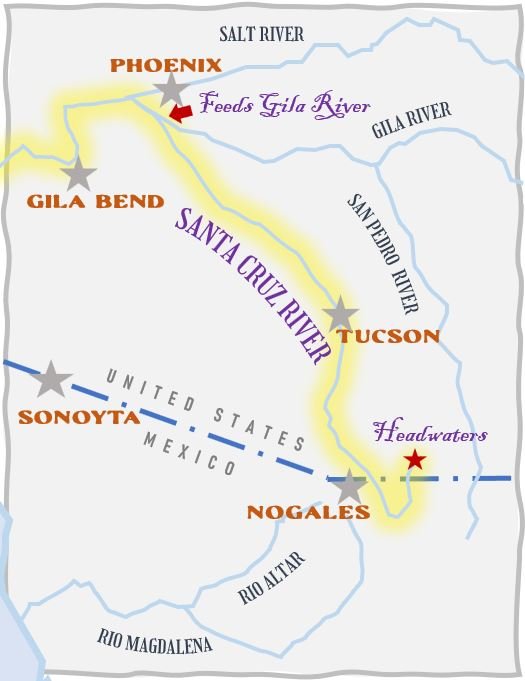

The Santa Cruz River starts in the United States, but crosses south into the state of Sonora, Mexico before heading north again into Arizona. It begins in the San Rafael Valley, flowing south just into Mexico before making a nearly 180-degree turn back into the United States. There, it flows from south to north, eventually joining with the waters of the Gila. The Santa Cruz provides critical habitat for threatened and endangered species including a wide variety of birds. Arizona has more than 140 bird species and has become a bird-watching destination. The Tucson Audubon Society has a guide to great locations on their site.

The Santa Cruz River and riparian corridor starts in the United States, crosses into Mexico, and runs north again through Tucson and empties into the Gila briefly before another tributary, the Salt River. The Gila finishes by joining the Colorado River at Yuma, AZ. No water from the Santa Cruz or any tributaries to the Colorado reach the Gulf of California any longer. It is completely consumed by farming irrigation, industrial, rural and city uses.

From the National Park Service:

“Where underlying bedrock slopes up, the water is forced to the surface. The O’odham situated their villages in these locations, known as “gaining reaches,” to take advantage of the reliable water source. Later settlers followed suit.

The river provided not only water for drinking and irrigation, but habitat for the complex web of life that supported human settlement. It contributed to every basket, meal, article of clothing, medicine, and cultural practice. Literally every item a person touched over the course of a lifetime connected back to the Santa Cruz River corridor.

Today, the cottonwood-willow environment along the Santa Cruz is one of the most rare and endangered habitats in the United States. The river‘s plant and animal communities and water quality are threatened by climate change and modern land use. The stretch of river that flows through Tumacácori is now composed almost entirely of treated effluent, released from the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Facility in Rio Rico, Arizona. Although this supplemental water source has supported the return of the endangered Gila topminnow (Poeciliopsis occidentalis), it is not safe for human consumption. Avoid contact.”